This is a deep question that has engaged the greatest minds since Socrates, Plato and Aristotle of Ancient Greece. Out of their quest to find absolute truths, the axiomatic method and the field of mathematics evolved. So, today we regard the statement “2 + 2 = 4” as an absolute truth that has universal acceptance.

However, as mathematicians attempted to expand the scope of absolute truth, paradoxes arose in dealing with infinite series and infinitesimal quantities, increasing the need for mathematical rigor. The quest for certainty intensified and the level of abstraction was increased to reduce the role of intuition in the formulation of the basic concepts. Through the nineteenth and early 20th century this quest for ultimate rigor intensified even more–creating a paralysis that was described by some as rigor mortis. Mathematical objects became increasingly abstract and remote from human experience. Some branches of mathematics became so esoteric that it was not always clear whether theorems generated from formal operations had any application or relation to the real world. Bertrand Russell captured this trend in his facetious statement:

Mathematics may be defined as the subject in which we never know what we are talking about, nor whether what we are saying is true.

Then, in 1931, Kurt Gödel enunciated his Completeness Theorems, revealing what are called “undecidable propositions.” These are mathematical statements that can neither be proved nor disproved using only absolute truths. That is, there are some theorems that cannot be proved using only a set of axioms that are accepted as absolutely true.

But what about truth outside the field of mathematics? Each of us is little more than a brain receiving information through our senses from an external world. Between us and the stimuli that reach our receptors is a large abyss that must be bridged by a process that “makes sense” of the incoming data. From birth we are gifted with a growing cognitive capacity to organize this information into stored memories and learned concepts. But this representation is fraught with flaws and inaccuracies that derive from two factors. The first of these is physiological. Our senses grasp only a small fraction of the information that is present in the external world.

The second factor obscuring our perception of absolute truth is manifest in the biases that are hardwired by evolution into our cognitive machinery. While these perceptual distortions arose to enhance our chances of survival, they carry some side effects that distance us from objectivity. For example, in some cases our senses sacrifice accuracy for speed, giving us fast-and-biologically-frugal approximations that present a flawed representation of reality.

Until recently, we were unaware of the extent to which these biases were skewing our perceptions, tacitly assuming that what we saw, heard, or felt was “truth”–described by Daniel Kahneman as WYSIATI (What You See Is All There Is.) However, recent research has made us conscious of these cognitive glitches. A growing list of these cognitive biases include, survivorship bias, confirmation bias and ingroup-outgroup bias. While some are inconsequential, others manifesting in tribalism, divisiveness, and genocide threaten the survival of our species. If you ask people whether Putin is justified in his invasion of Ukraine, you may get different answers depending upon where your respondent is located.

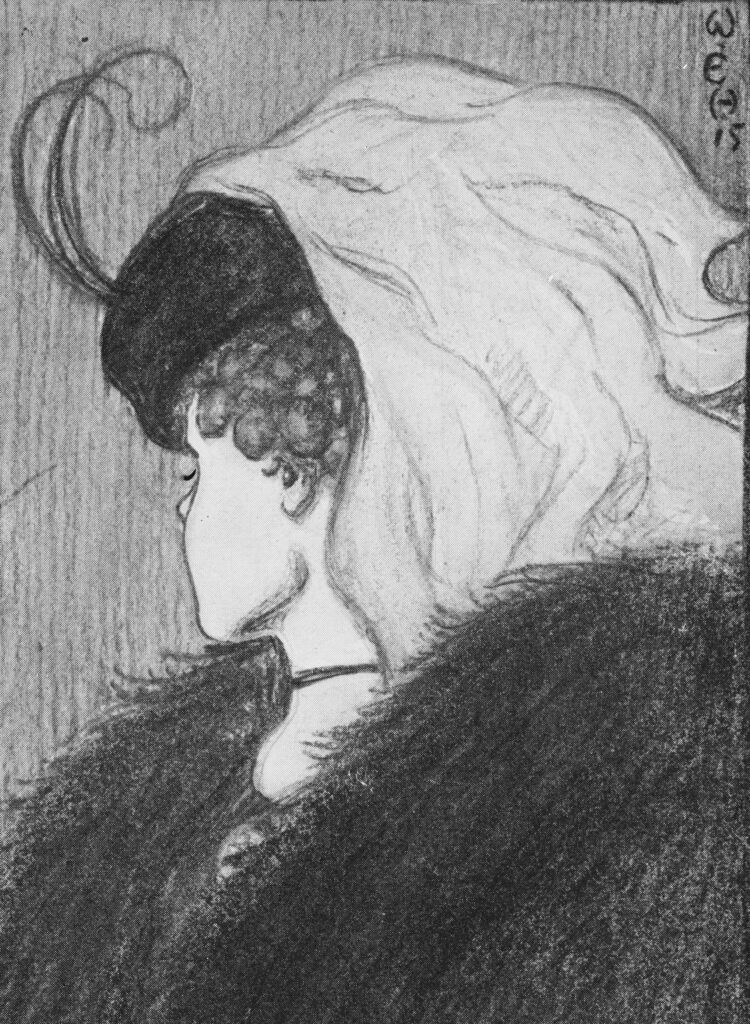

By the way, when you look at W. E. Hill’s sketch above, you may see an old lady or a young woman. Share this picture with friends and ask what they see. We all perceive the world differently–it’s a gift and a curse.